Fornicata

Ivan Cepicka

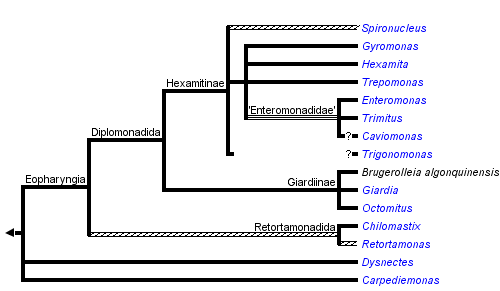

This tree diagram shows the relationships between several groups of organisms.

The root of the current tree connects the organisms featured in this tree to their containing group and the rest of the Tree of Life. The basal branching point in the tree represents the ancestor of the other groups in the tree. This ancestor diversified over time into several descendent subgroups, which are represented as internal nodes and terminal taxa to the right.

You can click on the root to travel down the Tree of Life all the way to the root of all Life, and you can click on the names of descendent subgroups to travel up the Tree of Life all the way to individual species.

For more information on ToL tree formatting, please see Interpreting the Tree or Classification. To learn more about phylogenetic trees, please visit our Phylogenetic Biology pages.

close boxIntroduction

Fornicata is a recently (Simpson 2003) recognized clade that belongs to the eukaryotic supergroup Excavata. Fornicates are unicellular heterotrophic flagellates with one or two karyomastigonts per cell. One karyomastigont bears one to four flagella. Fornicates exhibit several unusual characteristics, notably absence of classical mitochondria. Therefore, they were once considered to represent basal, primarily amitochondriate eukaryotes, so-called “Archezoa”. However, it has been shown that the presumably primitive fornicate cell arose rather by simplification and that Fornicata possess reduced mitochondria-related organelles.

The clade consists of four disparate lineages: free-living Carpediemonas and Dysnectes, both free-living and parasitic diplomonads (Diplomonadida), and almost exclusively parasitic retortamonads (Retortamonadida). Diplomonads, the best known fornicate group, comprise several important parasitic species including the human intestinal pathogen Giardia intestinalis. Interestingly, most diplomonads are diplozoic, i.e. their cells possess two identical and axially symmetrical sets of all cellular structures, though the symmetry is probably only superficial. Some diplomonads also use an alternative genetic code. The other fornicates, i.e. retortamonads, Carpediemonas and Dysnectes, are among the least studied eukaryotes.

Characteristics

Fornicata belong to the excavate taxa as defined by Simpson (2003). The ancestral number of flagella in the fornicate karyomastigont is probably four; however, the number of basal bodies and/or flagella has been reduced independently in several lineages (Carpediemonas, Dysnectes, Retortamonas, some diplomonads). One flagellum of the karyomastigont is directed posteriorly, in association with a ventral groove or tube-like cytostome when present (cytostomes have been reduced in Giardiinae and in Caviomonas), and it is accompanied by both microtubular and non-microtubular fibres. The morphological synapomorphy of Fornicata is an arched fibre B, which is a non-microtubular fibre in the mastigont typical for some excavates. However, the character has been lost in diplomonads, the biggest fornicate group. Moreover, particular fornicate lineages differ considerably in morphology and cell structure. It is, therefore, currently impossible to define Fornicata on the basis of morphology, and monophyly of the whole group has been demonstrated solely by molecular-phylogenetic studies.

All members of Fornicata are anaerobic or microaerophilic. As Fornicata are closely related to also anaerobic Parabasalia and Preaxostyla, the anaerobiosis is most probably ancestral for all three groups (collectively referred as Metamonada). Similar to many other anaerobic eukaryotes, fornicate cells lack some organelles, notably typical mitochondria. As in the other anaerobes, it now seems to be clear that Fornicata once bore mitochondria or mitochondrion-related organelles that have been reduced secondarily. A mitochondrion-related organelle, called the mitosome, has been identified in Giardia intestinalis. The mitosome is a small, genome-lacking organelle surrounded by two membranes. The mitosome of Giardia has lost most typical mitochondrial functions, including metabolism of pyruvate and the electron transport chain, and its only known function is the synthesis of iron-sulphur clusters. Putative mitochondria-related organelles have also been described in Carpediemonas membranifera and Dysnectes brevis, though their nature remains unclear. Retortamonads are one of the last eukaryotic groups where no mitochondrion-related organelle has been found so far; however, this probably reflects the very limited knowledge on this group.

Diplomonadida

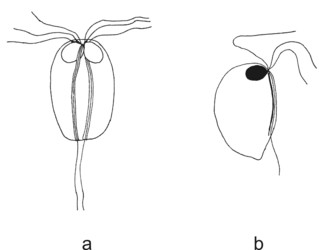

Diplomonad cells have lost some typical excavate and fornicate characters, and their morphology appears derived. With respect to the number of karyomastigonts per cell, the diplomonads can be divided into diplozoic and unizoic ones (see Figure 1). Most diplomonads are diplozoic, i.e. they have all cellular structures doubled, and the cell looks axially symmetric. Interestingly, the symmetry of the two karyomastigonts of diplozoic diplomonads seems, at least in the case of Giardia intestinalis, to be only superficial. In Giardia the two nuclei of a single cell differ in karyotype and mastigonts exchange a flagellum during each cell cycle. By contrast, unizoic diplomonads, i.e. genera Enteromonas, Trimitus and Caviomonas, collectively known as “enteromonads”, possess only one karyomastigont and cytostome (which was lost in Caviomonas) per cell. The cytostome of “enteromonads” forms a groove on the ventral part of the cell.

Figure 1. Diplomonads. a - diplozoic diplomonad Hexamita. b - unizoic diplomonad Enteromonas. © Ivan Cepicka

Based on the presence or absence of cytostomes (homologous with the excavate ventral groove), diplozoic diplomonads have been divided into Hexamitinae and Giardiinae. Hexamitinae possess either tube-like cytostomes passing through the whole cell and opening posteriorly (Hexamita, Spironucleus, Gyromonas, Trigonomonas), or pocket-like grooves harboring three flagella (Trepomonas). Representatives of particular Hexamitinae genera are usually easily recognizable. The exceptions are the similar genera Hexamita and Spironucleus. They differ in the shape of nuclei (oval in Hexamita, kidney-shaped in Spironucleus) and slightly in the position of basal bodies. Several species, described originally as Hexamita, belong, in fact, to the genus Spironucleus. Giardiinae diplomonads (genera Octomitus, Brugerolleia and Giardia) have lost the cytostomes with the associated cytoskeleton, and their recurrent flagella pass through cytoplasm as naked axonemes. While the similar genera Octomitus and Brugerolleia resemble in appearance diplozoic Hexamitinae diplomonads, the genus Giardia possesses a rather modified morphology. The cell is dorso-ventrally flattened, and the anterior part of the ventral surface is modified into an adhesive disc. The disc is used in the attachment of Giardia trophozoites to the surface of the small intestine.

The life cycle of diplomonads includes a trophozoite and a cyst. The cysts of both diplozoic and unizoic diplomonads are four-nucleated, oval and are surrounded by a thick wall. The cysts are used in the transmission of diplomonads between hosts and in surviving unfavourable conditions in the case of free-living diplomonads. Mitosis of the diplomonad nucleus is semi-open. No sexual processes have been observed; however, there is genetic evidence of hybridization between distinct Giardia intestinalis genotypes.

Key to the diplomonad genera based on light-microscopic characters

- 1 (5) Cells are unizoic.

- 2 (3, 4) Four flagella per karyomastigont .......................................................Enteromonas

- 3 (2, 4) Three flagella per karyomastigont ............................................................Trimitus

- 4 (2, 3) Single flagellum per karyomastigont ...................................................Caviomonas

- 5 (1) Cells are diplozoic.

- 6 (14) Cytostomes present.

- 7 (8, 9) Two flagella per karyomastigont ..........................................................Gyromonas

- 8 (7, 9) Three flagella per karyomastigont ....................................................Trigonomonas

- 9 (7, 8) Four flagella per karyomastigont.

- 10 (11) Cytostomes pocket-like, each containing three flagella .........................Trepomonas

- 11 (10) Cytostomes tbe-like, each containing a single flagellum.

- 12 (13) Nuclei oval ............................................................................................Hexamita

- 13 (12) Nuclei kidney-shaped ........................................................................Spironucleus

- 14 (6) Cytostomes absent.

- 15 (16) Ventral adhesive dics absent ........................................Octomitus and Brugerolleia

- 16 (15) Ventral adhesive disc present ...................................................................Giardia

Retortamonadida

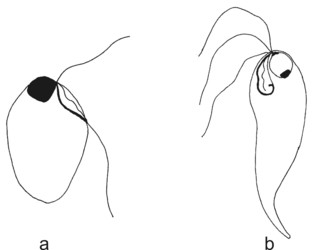

Retortamonadid cells are unikaryotic and possess a conspicuous apical cytostome (see Figure 2) associated with the posterior flagellum. Most retortamonadids possess a system of microtubules underlying the plasmatic membrane and forming a corset, though it seems that the microtubular corset has been lost in some Retortamonas species (Cepicka et al. 2008). Only two retortamonad genera, Retortamonas and Chilomastix, have been described so far. They differ mainly in the number of flagella and in the structure of the cytostome (Figure 2). The genus Retortamonas is biflagellate (though it bears also two barren basal bodies), and the distal part of the posterior flagellum emerges outside the cytostomal groove. The genus Chilomastix is quadriflagellate, and the short posterior flagellum is confined to the cytostomal groove. The life cycle of retortamonads includes a trophozoite and an uninucleate cyst. No sexual processes have been observed in retortamonads so far.

Figure 2. Retortamonads. a - Retortamonas. b - Chilomastix. © Ivan Cepicka

Carpediemonas and Dysnectes

Little is known about the two marine free-living fornicate genera. Both are biflagellated though Carpediemonas cells bear also a third, barren basal body.

Discussion of Phylogenetic Relationships

Fornicata are traditionally classified into Diplomonadida, Retortamonadida, Carpediemonas, and Dysnectes. Diplomonadida and Retortamonadida have been regarded as closely related and together they constitute the taxon Eopharyngia (the term refers to the extensively developed cytopharynx of diplomonads and retortamonads). The hypothesis of Eopharyngia was supported by molecular-phylogenetic studies which included sequences of Retortamonas and several diplomonad genera.

At first, the studies based on the SSU rRNA gene (Silberman et al. 2002; Kolisko et al. 2005; Keeling and Brugerolle 2006) indicated that diplomonads may not be monophyletic and that Retortamonas may be sister to the Giardiinae diplomonad lineage. However, the analysis based on the hsp90 gene showed that diplomonads are monophyletic and that Retortamonas forms their sister lineage, which was consistent with previous morphology-based hypotheses.

Sequence data of the second retortamonads genus, Chilomastix, have been obtained quite recently (Cepicka et al. 2008). Interestingly, instead of being specifically related to Retortamonas, Chilomastix branched with strong statistical support more basally and formed a sister branch to the Retortamonas , Diplomonadida clade. This means that Retortamonadida may not be monophyletic and that Diplomonadida may be, in fact, an internal lineage of Retortamonadida. In that case, ancestors of Diplomonadida must once have possessed retortamonadid morphological characters, notably the microtubular corset. An unpublished TEM study of Retortamonas suggests that the representatives of the genus for which the sequence data has been obtained lack the microtubular corset which further supports their close relationship with diplomonads. On the other hand, the microtubular corset has been reported from some other Retortamonas species, and it is probable that the genus is not monophyletic.

Former morphological hypotheses always assumed that the unizoic “enteromonads” are either sister to the diplozoic diplomonads, or form a basal paraphyletic grade. Based on the presence or absence of cytostomes, diplozoic diplomonads were divided into Hexamitinae and Giardiinae. While molecular-phylogenetic studies supported the division of diplozoic diplomonads into Hexamitinae and Giardiinae lineages (Keeling and Brugerolle 2006), it turned out that the phylogenetic position of “enteromonads” is rather interesting and was not predicted by any of the former hypotheses. In SSU rRNA and hsp90 trees, unizoic enteromonads form several independent branches within the Hexamitinae lineage (Kolisko et al. 2008). This close relationship is further supported by the use of a non-canonical genetic code (TAA and TAG triplets encode glutamine instead of stop codons) by Hexamitinae and “enteromonads” (Keeling and Doolittle 1996; Kolisko et al. 2008). It indicates that either diplozoic diplomonads arose several times independently from unizoic cells or that unizoic enteromonads arose several times independently from diplozoic diplomonads.

References

Cepicka, I., Kostka, M., Uzlíková, M., Kulda, J., and J. Flegr. 2008. Non-monophyly of Retortamonadida and high genetic diversity of the genus Chilomastix. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 48(2):770-775.

Keeling, P. J., and W. F. Doolittle. 1996. A non-canonical genetic code in an early diverging eukaryotic lineage. EMBO J. 15: 2285-2290.

Keeling, P.J., and G. Brugerolle. 2006. Evidence from SSU rRNA phylogeny that Octomitus is a sister lineage to Giardia. Protist 157: 205-212.

Kolisko, M., Cepicka, I., Hampl, V., Kulda, J., and J. Flegr. 2005. The phylogenetic position of enteromonads: a challenge for the present models of diplomonad evolution. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 55: 1729-1733.

Kolisko, M., Cepicka, I., Hampl, V., Leigh, J., Roger, A. J., Kulda, J., Simpson, A. G. B., and J. Flegr. 2008. Molecular phylogeny of diplomonads and enteromonads based on SSU rRNA, α-tubulin and HSP90 genes: implications for the evolutionary history of the double karyomastigont of diplomonads. BMC Evol. Biol. 8: 205.

Silberman, J. D., Simpson, A. G. B., Kulda, J., Cepicka, I., Hampl, V., Johnson, P. J., and A. J. Roger. 2002. Retortamonad flagellates are closely related to diplomonads — implications for the history of mitochondrial function in eukaryote evolution. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 19: 777-786.

Simpson, A. G. B. 2003. Cytoskeletal organization, phylogenetic affinities and systematics in the contentious taxon Excavata (Eukaryota). Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 53: 1759-1777.

Simpson, A. G. B., and D. J. Patterson. 1999. The ultrastructure of Carpediemonas membranifera (Eukaryota) with reference to the "excavate hypothesis". Eur. J. Protistol. 35: 353-370.

Simpson, A. G. B., Roger, A. J., Silberman, J. D., Leipe, D. D., Edgcomb, V. P., Jermiin, L. S., Patterson, D. J., and M. L. Sogin. 2002. Evolutionary history of "early-diverging" eukaryotes: the excavate taxon Carpediemonas is a close relative of Giardia. Mol. Biol. Evol. 19: 1782-1791.

Yubuki, N., Inagaki, Y., Nakayama, T., and I. Inouye. 2007. Ultrastructure and ribosomal RNA phylogeny of the free-living heterotrophic flagellate Dysnectes brevis n. gen., n. sp., a new member of the Fornicata. J. Eukaryot. Microbiol. 54: 191-200.

Title Illustrations

| Scientific Name | Dysnectes brevis |

|---|---|

| Specimen Condition | Live Specimen |

| Life Cycle Stage | trophozoite |

| Image Use |

This media file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution License - Version 3.0. This media file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution License - Version 3.0.

|

| Copyright |

© 2008

|

| Scientific Name | Carpediemonas bialata |

|---|---|

| Location | Botany Bay (Sydney, Australia) |

| Specimen Condition | Live Specimen |

| Life Cycle Stage | trophozoite |

| Source | Carpediemonas bialata |

| Source Collection | Micro*scope |

| Image Use |

This media file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike License - Version 2.5. This media file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike License - Version 2.5.

|

| Copyright | © Josef Brief |

| Scientific Name | Chilomastix caulleryi |

|---|---|

| Specimen Condition | stained with protargol |

| Identified By | Ivan Cepicka |

| Image Use |

This media file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial License - Version 3.0. This media file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial License - Version 3.0.

|

| Copyright |

©

|

| Scientific Name | Giardia cf. muris from Mesocricetus auratus |

|---|---|

| Specimen Condition | stained with protargol |

| Identified By | Ivan Cepicka |

| Life Cycle Stage | trophozoite |

| Image Use |

This media file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial License - Version 3.0. This media file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial License - Version 3.0.

|

| Copyright |

©

|

About This Page

This page is being developed as part of the Tree of Life Web Project Protist Diversity Workshop, co-sponsored by the Canadian Institute for Advanced Research (CIFAR) program in Integrated Microbial Biodiversity and the Tula Foundation.

Department of Zoology, Charles University in Prague

Correspondence regarding this page should be directed to Ivan Cepicka at

Page copyright © 2009

Page: Tree of Life

Fornicata.

Authored by

Ivan Cepicka.

The TEXT of this page is licensed under the

Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial License - Version 3.0. Note that images and other media

featured on this page are each governed by their own license, and they may or may not be available

for reuse. Click on an image or a media link to access the media data window, which provides the

relevant licensing information. For the general terms and conditions of ToL material reuse and

redistribution, please see the Tree of Life Copyright

Policies.

Page: Tree of Life

Fornicata.

Authored by

Ivan Cepicka.

The TEXT of this page is licensed under the

Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial License - Version 3.0. Note that images and other media

featured on this page are each governed by their own license, and they may or may not be available

for reuse. Click on an image or a media link to access the media data window, which provides the

relevant licensing information. For the general terms and conditions of ToL material reuse and

redistribution, please see the Tree of Life Copyright

Policies.

- First online 02 September 2008

- Content changed 02 September 2008

Citing this page:

Cepicka, Ivan. 2008. Fornicata. Version 02 September 2008 (under construction). http://tolweb.org/Fornicata/121182/2008.09.02 in The Tree of Life Web Project, http://tolweb.org/

Go to quick links

Go to quick search

Go to navigation for this section of the ToL site

Go to detailed links for the ToL site

Go to quick links

Go to quick search

Go to navigation for this section of the ToL site

Go to detailed links for the ToL site