A sea urchin, bottom side up, found in Croatia. There are more than 700 different species of sea urchins.

Classification of the Sea Urchin

- Kingdom: Anamalia

- Phylum: Echinodermata

- Class: Echinoidea

General Description

A sea urchin found in Sangenjo, Galicia, Spain. Note the tube feet sticking out between the spines. © 2005 Janek Pfeifer

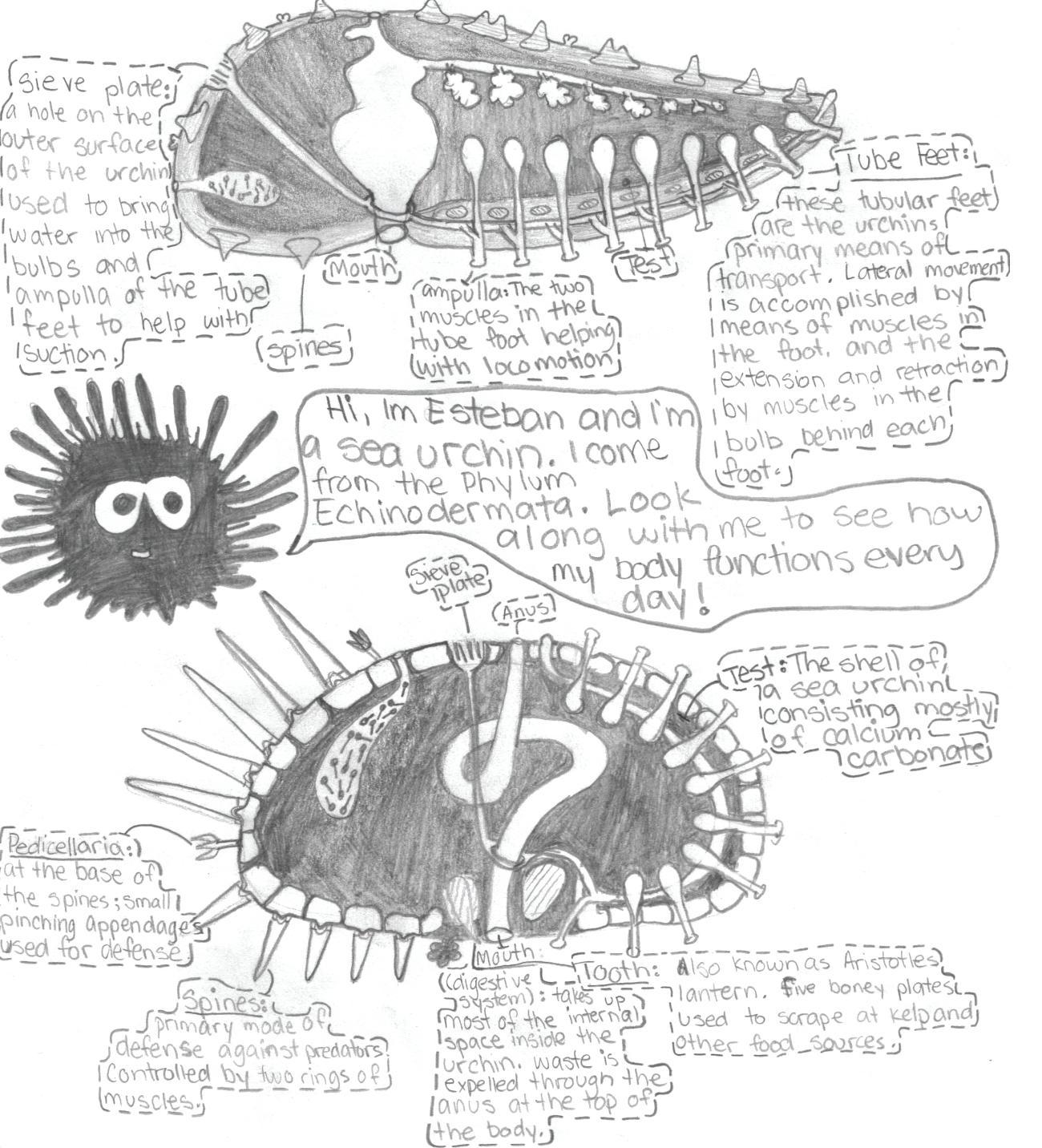

Sea urchins are sea creatures that live in oceans all over the world. Similar to sea stars, sea urchins have a water vascular system. Their spherical shape is typically small, ranging from about 3 cm to 10 cm in diameter, and their bodies are covered with a spiny shell. The skeleton of a sea urchin is also known as the test. The shells within the test of these creatures are made up of packed, fitted plates which protect them from being damaged. As for the spines outlining their shell, these are movable and help the sea urchin to camouflage or protect itself from predators. Sea urchins can vary greatly in colour. Some of the most frequently seen colours are black, red, brown, purple and light pink. On the bottom side of a sea urchin there are five teeth that these organisms use to ingest algae and break down other foods they consume to survive. These five teeth continually grow throughout the sea urchin’s life. On the outside of their body, they also have hundreds of transparent tubes that emerge which allow them to stick to the bottom of the ocean or to move at a very slow pace. These unusual tubes are called “tube feet.” Their tube feet are much longer than the spines outlining their shells and they are also used by the sea urchin to trap food and in respiration.

Reproductive Characteristics

Sea urchins are sexually reproducing organisms. First millions of eggs are released by the females and they unite and fuse with the sperms released by the males. The unification of the jelly-coated egg and the tiny sperm usually occurs outside the female’s body; however in some rare cases the fertilization will take place within the female’s body. Once the fertilization of the gametes occurs, a larva is formed. This larva is also known as a pluteus. The sex of the larva is impossible to distinguish until it itself begins to release either eggs or sperms during its adulthood. The average size of the eggs that female sea urchins produce is about 100-150 microns, and the average size of the sperms is about 1×5 microns plus the tail. The time that adult sea urchins start reproducing is during the ages of 2-5 years.

Habitat

Sea urchins can be found all over the world in all oceans, warm or cold water. They live in a variety of environments in many different parts of the world. Some common places they live are in rock pools and mud, on wave-exposed rocks, on coral reefs in kelp forests and in sea grass beds. Sea urchins also commonly lodge themselves half way into the surface of sand, mud or holes. This way they can be protected from large waves or currents. Sea urchins also live in areas where they can find sources of algae, sea grass, seaweed and other foods they can consume. One other very important characteristic of the sea urchin is that it is nocturnal. Sea urchins will usually hide in holes or crevasses during the day and only feed at night. A common place to find a sea urchin as well is in coral reefs. Examples of where sea urchins are very commonly found are on the reefs of Hawaii, of the Caribbean and of Australia.

Adaptations to the Environment

Sea urchins have several adaptations to help them survive. To protect themselves from predators, sea urchins will react immediately if something sharp touches their shell and they will point all of their spines towards the area being poked. They are also light-sensitive. This is why they are nocturnal. This light sensitivity also allows sea urchins to move their spines in reaction to shadows. In order to protect themselves from being swept away from the powerful ocean currents and waves, sea urchins lodge themselves into holes or crevasses. Finally sea urchins, somewhat like starfish, have a certain regenerative ability. If a spine is damaged or lost, a sea urchin can re-build it. However if there is too much extensive damage to the test, the sea urchin won’t be able to heal it.

Importance in the Environment

Like most creatures, sea urchins are vital for the survival of other living creatures surrounding them. They have many predators and due to this, if the sea urchin population decreased, the sea creatures that feed on them might begin to die out as well. A few predators that feed on sea urchins are sea otters, star fish and humans. However for there to be a healthy balance in their environment, it’s very important that the population of sea urchins do not decrease or increase all that much. This problem occurred in the 1980’s in the Caribbean when the sea urchin population began to increase at an extremely rapid rate. At one point there was almost a density of eighty sea urchins per square meter. This immense number of sea urchins began to eliminate the sea weed which lived in the same area. They were also eroding the coral reef. Luckily before any huge damage had occurred, there was a mass die-off of sea urchins in the area believed to be caused by a water-carried disease. Sea urchins have also been reported to cause erosion of reefs in places such as the eastern Pacific, Kenya and the Red sea. So although sea urchins are important to the survival of an ecosystem, they can also become dangerous in great numbers.

Endangered?

At the moment sea urchins are very populous and located all over the world in many different oceans. Therefore they seem to be in no immediate danger of disappearing or becoming endangered in general. However in the past sea urchins have shown mass mortality due to an increased amount of pollution in the oceans and also due to an increased amount of fishing by humans. Hurricanes and a rise in the temperature of water have also wiped out a great amount of sea urchins. Evidently sea urchins are very susceptible to change, and with global warming, which is changing the temperature of the oceans and increasing the amount of tropical storms, they may become endangered in the future.

The Sea Urchin Quiz

- Where do sea urchins live?

- In the Atlantic Ocean

- In the Pacific Ocean

- In all oceans

- In the Indian Ocean

- Typically how large are sea urchins?

- 3-10 cm in diameter

- 11-15 cm in diameter

- 15-20 cm in diameter

- None of the above

- What do sea urchins eat?

- Live fish

- Bacteria

- Humans

- Bits of plants, animals, algae and seaweed

- How many teeth do sea urchins have?

- 2 teeth

- 3 teeth

- 4 teeth

- 5 teeth

- When sea urchins are touched by a sharp object they will…

- Go limp, play dead

- Point all their spines to the area being touched

- Attempt to swim away

- Emit a type of poison into the water

- How many types of sea urchins are there?

- 10

- About 100

- Over 700

- Around 10000

- Where is a sea urchin’s mouth located?

- On it’s side

- On its bottom

- On its top

- It doesn’t have a mouth.

Answers: 1. c – 2. a – 3. d – 4. d – 5. b – 6. c – 7. b

Diagram of a Sea Urchin’s Anatomy

Artist rendition of a sea urchin's anatomy. © 2008 Tara Monaghan

Information on the Internet

- Sea Urchins Col, Jeananda. 2000-2008. Enchanted Learning. Accessed 12 Sept. 2008.

- Purple Sea Urchin Minnesota Zoo. Accessed 12 Sept. 2008.

- Sea Urchin Embryology Stanford University. Accessed 12 Sept. 2008.

- Sea Urchins and Sand Dollars Net Industries. Accessed Sept. 2008.

- Sea Urchins Think Quest. Oct. 2002. Accessed 12 Sept. 2008.

Go to quick links

Go to quick search

Go to navigation for this section of the ToL site

Go to detailed links for the ToL site

Go to quick links

Go to quick search

Go to navigation for this section of the ToL site

Go to detailed links for the ToL site